Crowds of exotic visitors filled the streets of Warsaw on 31 July 1955, marking the beginning of the 5th World Festival of Youth and Students. The participants made their way around the city in colourful processions under slogans such as ‘Fighting for Peace and Friendship Among Nations’ or ‘Solidarity with Freedom-Fighting Youth in Colonial Countries’. Images of exotic cultures and their representatives supported the propaganda rhetoric, providing impressive camouflage for what was really neo-colonial policies and ambitions on the part of the Soviet Union, which strove to subordinate countries getting rid of their hitherto colonisers.

More than twenty years earlier, similar images appeared in the popular magazine Morze [The Sea], organ of the pre-war Polish Naval and Colonial League, which featured photo stories from exotic locations, seducing the Polish reader with images of sunny shores, impossible-to-get fruits, and fascinating natives. Published next to ideological texts, they illustrated what was presented as a paradisiacal no-man’s land that Poland can and should reach for, either through direct colonisation or international negotiations.

Witch, Witch, Where Do You Fly? evokes those two moments of the Polish iconosphere’s strong saturation with exoticism. We interpret them as attempts to colonise the image by exploiting the allure of the distant Other. The featured photographs pay witness to the spectacularity of the ideological message and allow the viewer to trace fractures in its structure.

The third instalment of the Ideoses exhibition series was inspired by the history of a frieze that dominated the space of festival Warsaw. Screening the city’s ruins from view, it became its façade and showpiece. Designed by a group of young visual artists under the direction of Henryk Tomaszewski and Wojciech Fangor, the monumental, nearly 400-metre-long decorative-propaganda frieze stretched on huge scaffoldings along Marszałkowska Street, from the corner of Sienkiewicza to Aleje Jerozolimskie. It was one of the elements of the city’s rich visual setting, which ranged from mural paintings, through the flags of participating countries and banners of political organisations, to lanterns, paper doves, exotic monkeys, lions and Chinese dragons. Besides photographs distributed by the press, the festival’s impressive logo is another example of a visual propaganda war — this time fought in public space. The frieze’s modern form was an expression of the liberalisation of the communist state’s policies towards art which, with the propaganda content it carried, made it an emblem of a political opening towards the Other — both the culturally exotic and the visually modern. Thus besides the famous Arsenal exhibition, which took place concurrently with the festival, the frieze became one of the symbols of the post-Stalin ‘Thaw’ that ushered in previously forbidden styles.

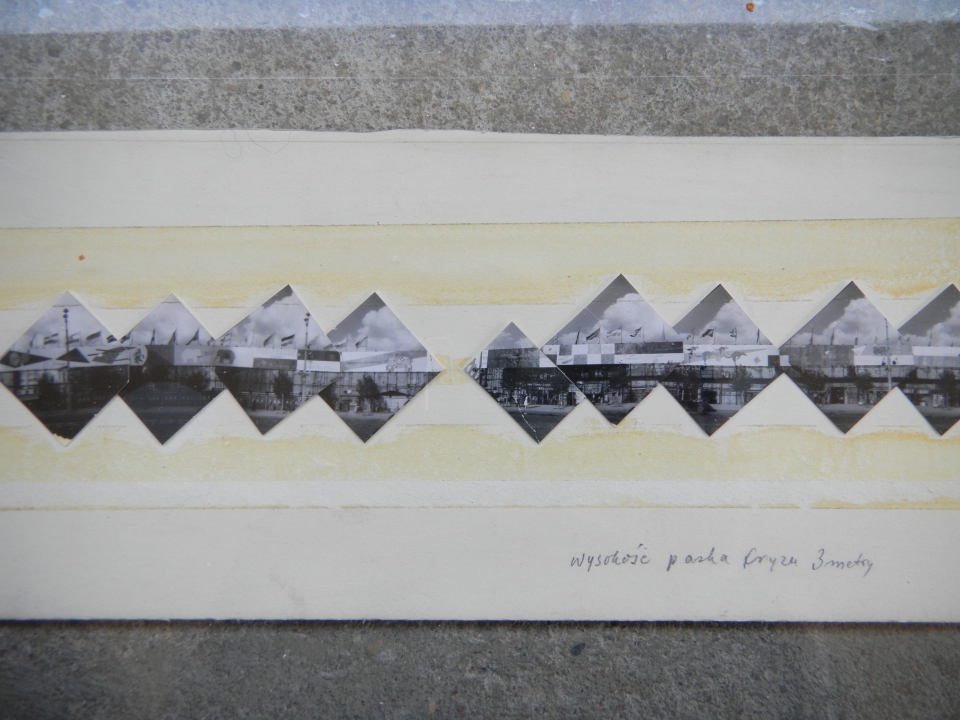

More than fifty years later, the frieze can only be viewed in photographs. The object’s only complete surviving documentation is a photographic collage by Henryk Tomaszewski, composed of miniature contact prints. Tomaszewski’s piece is a document of the past, in which the original’s artistic meaning, related to its public context, has been effaced. Similarly, propaganda images from before the war and from the 1950s today maintain documentary status only. Searching in the past for examples of the relationship with an exotic Other, we encounter fragments of a bygone reality, documents, reconstructions, accounts.

The exhibition aims not so much to confer an artistic status upon the featured images as to consider them from the viewpoint of a comprehensive anthropology of visuality. The decision not to present ‘works of art’ per se situates the show in the field of archaeology, turning the curator into a prospector for images hidden under the layers of historical and political meanings.

The exhibition’s design, created by architects Gronkiewicz and Wasilkowska, transfers the presented items from their proper central place to a marginal one — under the stairs, showing how a former façade becomes the background. The display construction that has ‘absorbed’ the show creates a peculiar situation for viewing propaganda images, highlighting, experientially, a disturbing moment of confrontation with the Other. At the same time, it is place that opens the perspective to the final piece of the puzzle: the Palace of Culture, one of the key features of the 1955 festival’s scenography, today a major vestige of former Soviet colonisation.

More info about the exhibition at

www.ideozy.blogspot.com

Artists:

Henryk Tomaszewski, Kacper Gronkiewicz, Aleksandra Wasilkowska

Curators:

Magdalena Kobus, Katarzyna Kucharska, Katarzyna Kuczyńska, Aleksandra Zbroja, Justyna Żelasko

Exhibition is on from 23 January through 7 February 2010

Tuesday — Saturday, 16.00–19.00

Exhibition is accompanied by Prof Andrzej Turowski’s lecture, You’ve Taken the Masks and Given Us Trash

Museum of Modern Art

Pańska Street 3, Warsaw

21 January 2010, 16.00